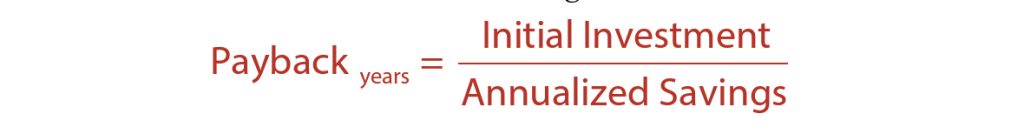

Simple payback, often referred to just as payback, describes the length of time needed for the savings generated by a resource efficiency project to return the initial investment made. It is calculated using the formula:

Thus, an investment of US$1,000 that yields regular annual savings of US$500 has a payback of two years. The annualized saving could be determined by a number of uneven cash flows, e.g. US$250 in year 1 and US$750 in year 2; here, the payback period is determined by adding up successive savings in the cash flow until they match the investment. If we are interested in the payback in months, then we would multiply the annual payback by 12.

A fractional payback is only strictly correct where our savings are continuous throughout the year (e.g. if I install new energy-efficient lamps the saving occurs every day the lighting is used). On the other hand, if the saving results from a discrete payment at the end of the year (e.g. a waste collection charge that is levied annually), then the payback period will be a precise number of years, even if the final saving exceeds the amount needed to cover the investments. Thus, if I have invested US$1,000 and this results in savings of US$600 at the end of year 1 and US$600 at the end of year 2, strictly speaking, the payback is two years, not 1.7 years as it won’t be until year 2 that the investment is repaid.

The saving is a net figure, that is to say, interest or other finance charges are included, unlike most other most methods of financial appraisal. We should also allow for tax in our savings. In other words, if these savings result in an increase in profit which is taxed, we would usually use the lower after-tax cash flows that are created by the investment. Alternatively, if we have a tax benefit – such as an enhanced capital allowances or depreciation – as a result of our investment, the net savings should be increased by the tax benefit.

The problem with payback

Despite its widespread use, payback is a very poor method of evaluating investments in energy or resource efficiency projects and is only really suitable as a high-level indicator of project risk rather than as a method of financial appraisal. Payback may be helpful when we have a return on investment of less than a year, where other measures of financial performance such as IRR are unsuitable, but should otherwise be avoided.

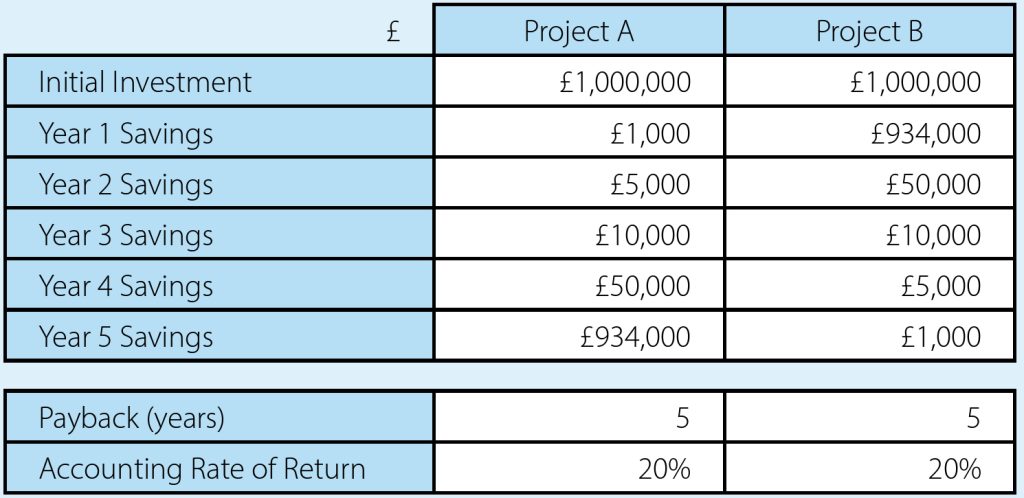

Consider the two projects below. They both have identical payback periods of five years (and the same Accounting Rate of Return, ARR, of 20%). Clearly, project B is much more desirable as it makes significantly greater savings earlier on, whereas project A defers almost all the savings until much later on.

Payback is unsuitable for comparing investment options because it fails to consider the timing of the savings within the payback period.

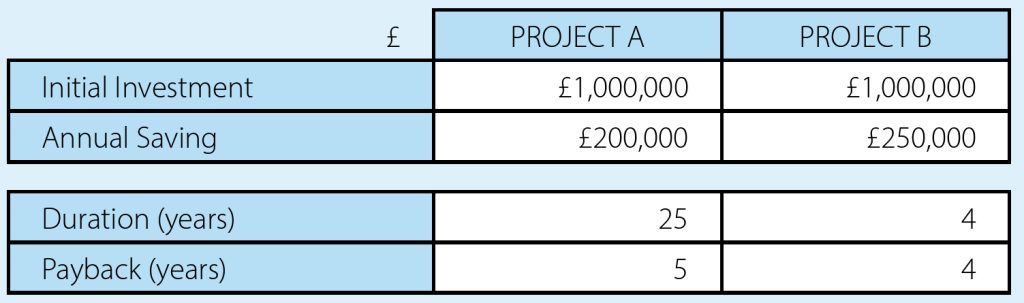

Now consider the two alternative investments below:

It would appear that project B with a shorter payback of four years is more attractive than project A. However, project B has a duration of just four years, so it adds no value at all to the organization as it only just covers its costs. Project A, on the other hand, continues to deliver savings for 20 years after it has paid for itself. Clearly, Project A is the better investment choice, even though it has a longer payback.

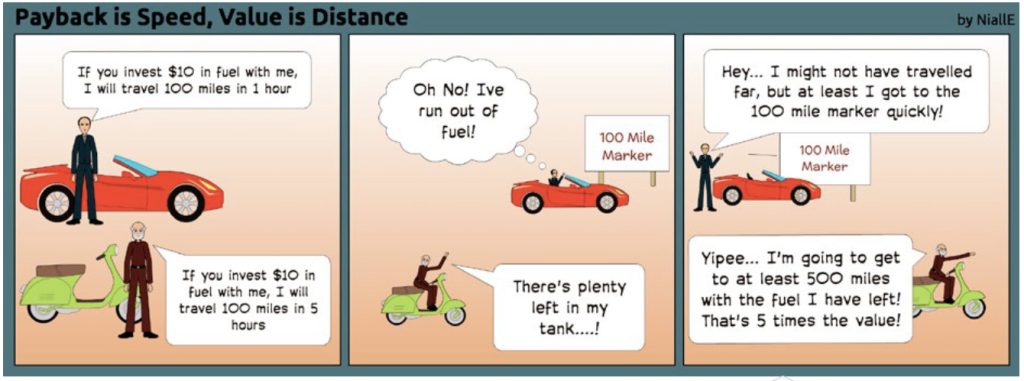

This example forms the basis of the cartoon below.

Payback is unsuitable for comparing investment options because it fails to consider the duration of the savings beyond the payback period.

However, the payback does provide a measure of the risk of a project. Clearly, a project which pays for itself quickly is has less uncertainty around it than one which takes a long time to return the initial investment. Given two projects whose financial performance is similar, then payback can help us make the final decision.Don’t just take my word for it. According to Capital Budgeting[1]:

Payback is a very unsophisticated and misleading measure and it is not recommended for accepting or rejecting projects

So what are the alternatives to payback? Techniques such as Net Present Value discount future savings compared to immediate savings, in order to favour immediate returns. The Internal Rate of Return is another widely-used measure of investment return. The strengths, weaknesses, “gotchas” and applicability of these techniques are fully explained in the Finance chapter of my book, Energy and Resource efficiency without the tears – the complete guide to adding value and sustaining change in an organisation, available free of charge on this site.

[1] Dyananda, Don. Capital Budgeting: financial appraisal of investment projects (Cambridge University Press, 2002). ISBN 978-0-521-52098-0

0 Comments