The English language is rich with aphorisms that warn us to take care before we proceed: “look before you leap”, “better safe than sorry”, “first do no harm” and “prevention is better than cure”. This notion of caution, originating in the German concept of Vorsorgeprinzip, loosely “forecaring principle”, lies at the heart of the debate about roles and responsibilities for resource efficiency.

The English language is rich with aphorisms that warn us to take care before we proceed: “look before you leap”, “better safe than sorry”, “first do no harm” and “prevention is better than cure”. This notion of caution, originating in the German concept of Vorsorgeprinzip, loosely “forecaring principle”, lies at the heart of the debate about roles and responsibilities for resource efficiency.

The precautionary principle states:

“When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically”.

The key here is whether there is an obligation to act in the absence of absolute scientific evidence pointing to possible harm. Clearly, if such an obligation exists, then organisations today that are contributing to climate change by, for example, emitting CO2 to the atmosphere or reducing forests, have an obligation to take measures to reduce the threat to the environment brought about by their actions. And the same principle applies to other forms of resource depletion, around water or biodiversity and so forth.

The definition of the precautionary principle above is taken from the “Wingspread Consensus Statement on the Precautionary Principle”, a conference in 1998 in the US where 32 participants including treaty negotiators, activists, scholars and scientists from the United States, Canada and Europe came together, under the auspices of the Science & Environmental Health Network, to discuss the principle[ sehn1998precautionary ]. Not only did they emphasise the notion that the principle “incites us to take anticipatory action in the absence of scientific certainty”, but also that “In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof”. In other words it is up to the proposer to demonstrate that no harm will arise from their proposal rather than for the public to prove otherwise.

No wonder then that this concept is hotly debated. In some jurisdictions like the European Union, the principle has been explicitly incorporated into the Lisbon Treaty as the basis for policy-making on the environment. The principle has also underpinned a number of international treaties, like the Montreal Protocol that banned ozone-depleting substances and the UN Conference on Development and the Environment in 1992. It is a concept that environmentalists support because it speaks to the idea that much harm to the environment cannot be easily undone so a cautious approach is rational.

Just as there are very committed proponents of the precautionary principle, there are also strong opponents. Some arguments against the principle point out that is it far too vague and so would be difficult to apply in law, while others resist the notion that organisations should bear the burden of risks that are not yet fully proven or that the slavish adoption of the principle would paralyse innovation and progress.

What is clear is that the precautionary principle undermines the strategy of climate change deniers who deliberately cherry-pick uncertainties in the science to convey the idea that human-induced climate change is merely an opinion rather than a conclusion with a foundation in scientific evidence beyond reasonable doubt. If the precautionary principle is applied then the presence of doubt or uncertainty cannot be used as the basis for inaction. No wonder then that Rex Tillerson CEO of ExxonMobil – an organisation which is known to have actively supported lobby groups which brief against climate change[ adam2009exxon ] – is so opposed to the principle. In a recent article on shale gas extraction by Fortune and CNN he is quoted as follows [ okeefe2012exxon ]:

“What’s happened is the tables have been turned around now to where we have to prove it’s not going to happen,” he says. “Well, that is a very dangerous exchange to get into because where it leads you from a regulatory and policy standpoint is to govern by the precautionary principle. And the precautionary principle will absolutely undermine the economy.” He adds, “If you want to live by the precautionary principle, then crawl up in a ball and live in a cave.”

This emphasis on the proposer having to prove the absence of harm, rather than the opponent having to prove harm, is what makes the precautionary principle so significant. Any organisation operating within the precautionary principle should establish positively that its actions will not harm, rather than proceed as if this is the case in the absence of data to the contrary. This shift in the burden on proof should enable us to make much better-informed decisions around issues of resource use by explicitly requiring us to examine the potential for harm in circumstances where there is doubt about the science.

That is not to say that the critics do not have some valid points about the precautionary principle. If the principle were applied slavishly to every decision then then it would certainly be an excessive burden on progress, so it needs to apply only where the risk of harm is believed to be great – in other words there has to be some scientific basis for the existence of significant danger, a threshold where it is triggered. For example, a recent effort in the US Courts to prevent the Large Hadron Collider being switched on because of a fear that the LHC would create an artificial black hole that would devour the world was dismissed because the plaintiff could not demonstrate a “credible threat of harm”[ court2010lhc ].

Other the Courts around the world are also helping to provide guidance on the application of the precautionary principle. At an international level, nation-states have been arguing about through the World Trade Organisation appeals processes about whether the principle can govern trade and at a national level the use of the principle in much environmental regulation has allowed it to be subject to legal clarification in many different jurisdictions. A very accessible commentary on this is by the Chief Judge of the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales in Australia, Justice Brian Preston, in his presentation to the Law Society of New South Wales in 2006[ preston2006law ]. Particularly useful is the explanation, on page 15 forwards, of the Australian Court’s decision in the case of Telstra Corporation Limited v Hornsby Shire Council[ NWSWLEC2006precaution ], which is one of the most comprehensive judicial exposition of the practical application of the precautionary principle.

The ruling effectively stated that there are two preconditions for the application of the precautionary principle: a threat of serious or irreversible environmental damage and scientific uncertainty as to the environmental damage (if there was scientific certainty then preventative action would inevitably need to be taken so the precautionary principle would be irrelevant). The ruling went on to describe that the evidence of harm needed to be based on data (not just hypothesis or speculation), that unanimous scientific support for the scenario envisaging harm is not required, and then describes the level of uncertainty that is needed for this evidence. If the two preconditions, threat and uncertainty, are met, then two further things flow: there is a shift in the burden of proof as the decision-maker must now assume that the threat of serious damage is a reality – putting the onus on the proponent of the development to prove otherwise. The second is the principle of preventative anticipation whereby action can be taken to prevent the threat before the reality and seriousness of the threat are fully known. In assessing what actions to take the risks associated with various alternative options should be considered, and prudence would suggest that a margin of error should be applied in favour of the environment where there is uncertainty. Importantly the action taken should be sensible and proportionate to the risk identified.

The ruling then goes on to state that the precautionary principle is just one tool in decision-making and that there are other principles of sustainable development that are relevant in any decision. Alan Randall’s excellent book “Risk and Precaution” [ randall2011precaution ] provides a very readable, comprehensive overview of the arguments for and against the precautionary principle and suggests how the precautionary principle can be integrated into everyday business decision-making alongside other risk-management processes using criteria such as those set out above.

Rex Tillerson’s fear-mongering characterisation of the precautionary principle as a destroyer of civilisation does no favours to businesses as a whole – or for that matter to the levels of trust that stakeholders have in ExxonMobil. In fact the precautionary principle as a common-sense approach to risk, with the kind of legal nuances set out above, protects and enhances the value of shareholders as much as it protects the environment. What would the value of the asbestos industry be today if the precautionary principle had been applied? Hundreds of companies make products much, much more inherently dangerous than asbestos – explosives, poisons, radioactive materials – and their businesses prosper to this day. What destroyed 98% of shareholder value in the asbestos industry was denial of the threat posed by the product, resulting in ineffective, late, complacent and reactive approach to scientific uncertainty[ sells1994asbestos ]. The antidote to this denial is the precautionary principle, which forces executives to examine the implications of decisions which could lead to great, but uncertain, harm. Surely this examination can only be in the interest of shareholders. If it can be demonstrated that no harm arises then the business can proceed with its plans – on the other hand if harm does arise it is in the interest of the shareholder that this potential risk is reduced.

One of the most significant regulatory examples of the precautionary principle can be seen in the REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and restriction of Chemicals)regulations in Europe, which requires producers (and importers) of chemicals to register every chemical they produce and assess its toxicity. Effectively what this regulation – and the precautionary principle as a whole – does is to shift the burden for ensuring public safety from government to businesses. Rather than regulators having to prove potential harm from substances, companies have to prove that their products are safe, and if there are toxicity or other issues, that the benefits outweigh the risks.

The precautionary principle also provides us with a very compelling argument to mitigate the environmental risks we confront in the absence of absolute certainty of the threat. One illustration I have used on many occasions with audiences who are not yet convinced of the reality of climate change is reproduced below:

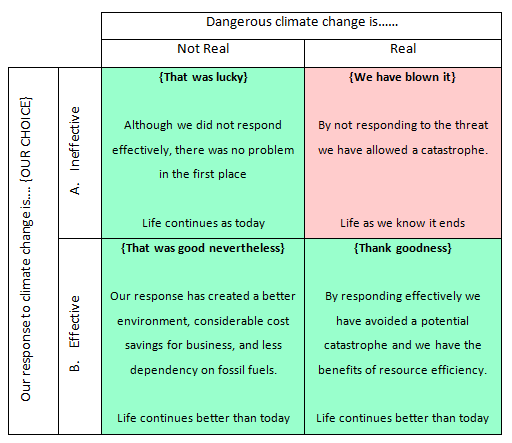

Figure 22 Choose A or B: an illustration of the precautionary principle as it relates to climate change. The vertical columns represent the uncertainties we have about dangerous climate change (is it real or not), over which we have no direct influence. The horizontal rows represent the choices we have (to act effectively to mitigate climate change or not), over which we do have control.

The important thing to convey in using this illustration is that we can only influence which row we choose (i.e. to make an effective response or not). The column represents what we are uncertain about (whether climate change is real or not). Clearly we want to avoid the red box – where life as we know it comes to an end. Thus the only rational choice is to take effective action on climate change, despite uncertainties in the science.

The observant reader will note that there is no “downside” portrayed from the bottom left box, where dangerous climate change is not real but we have nevertheless substantially transformed our businesses to reduce emissions and adapt to rising temperatures. While individual businesses, such as those based on the unabated combustion of fossil fuels, may well see a large reduction in their value unless they change the core business model, the majority of businesses will gain from resource efficiency to address climate change. That is because using less energy and creating less waste reduces costs; delivering more efficient products will provide competitive advantage; the new technology gold-rush to mitigate carbon emissions will create countless business opportunities and thousands of jobs; and anticipating rather than reacting to regulation will create greater degrees of freedom for business operations extending, rather than diminishing, their license to operate and innovate.

Further reading

[amazon_enhanced asin=”0521759196″ /]

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks